Florida Trend, February 2024 Issue: Daycare Dilemma

Laura Lyon and Michael Fechter | Florida Trend

Feb 12, 2024

Rising costs and the expiration of pandemic-era subsidies have Florida childcare centers and families in a crunch. State and federal lawmakers have limited options on the horizon as employers look to their own solutions.

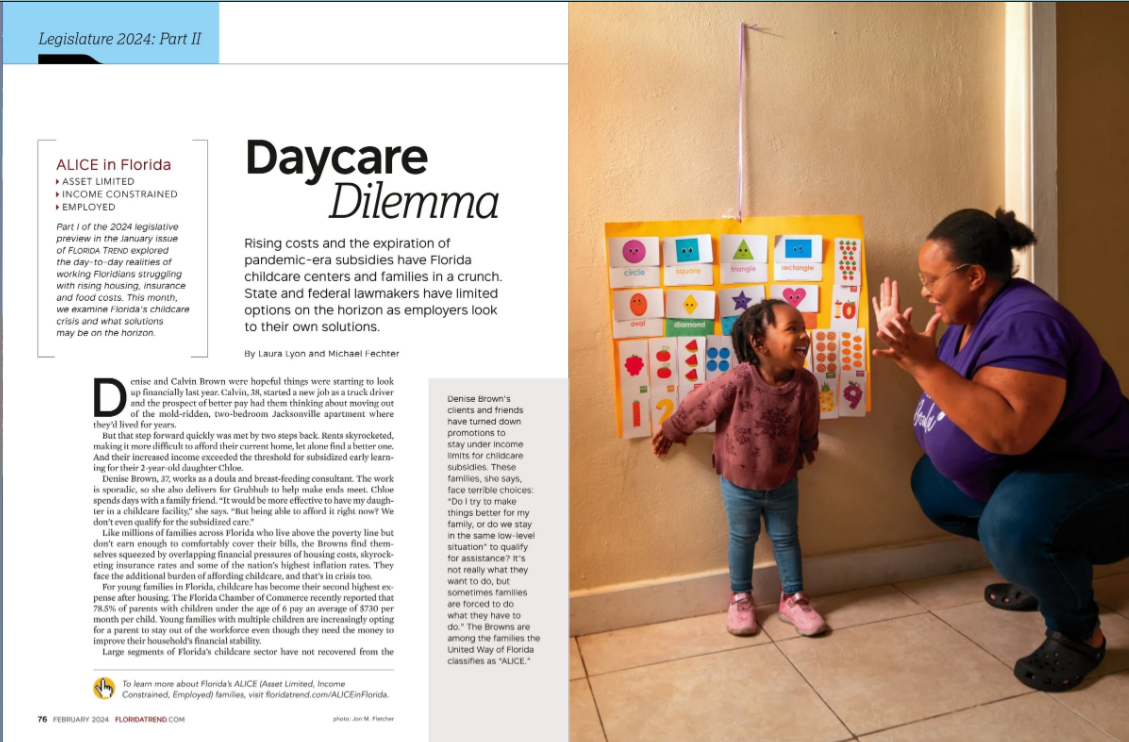

Denise and Calvin Brown were hopeful things were starting to look up financially last year. Calvin, 38, started a new job as a truck driver and the prospect of better pay had them thinking about moving out of the mold-ridden, two-bedroom Jacksonville apartment where they’d lived for years.

But that step forward quickly was met by two steps back. Rents skyrocketed, making it more difficult to afford their current home, let alone find a better one. And their increased income exceeded the threshold for subsidized early learning for their 2-year-old daughter Chloe.

Denise Brown, 37, works as a doula and breast-feeding consultant. The work is sporadic, so she also delivers for Grubhub to help make ends meet. Chloe spends days with a family friend. “It would be more effective to have my daughter in a childcare facility,” she says. “But being able to afford it right now? We don’t even qualify for the subsidized care.”

Like millions of families across Florida who live above the poverty line but don’t earn enough to comfortably cover their bills, the Browns find themselves squeezed by overlapping financial pressures of housing costs, skyrocketing insurance rates and some of the nation’s highest inflation rates. They face the additional burden of affording childcare, and that’s in crisis too.

For young families in Florida, childcare has become their second highest expense after housing. The Florida Chamber of Commerce recently reported that 78.5% of parents with children under the age of 6 pay an average of $730 per month per child. Young families with multiple children are increasingly opting for a parent to stay out of the workforce even though they need the money to improve their household’s financial stability.

Large segments of Florida’s childcare sector have not recovered from the COVID-19 pandemic shutdown and for the past three years have been stabilized by an infusion of billions of federal dollars from the American Rescue Plan. But the last of that funding will be distributed this year and both childcare advocates and fiscal watchdogs say in the months to come, centers might start closing.

“We’ve been in crisis for a really, really, really long time,” says Heather Siskind, CEO of the non-profit Jack & Jill Center in Broward County, which has served working families since the 1940s.

In late 2023, both Florida TaxWatch and the Florida Chamber of Commerce were sounding the alarm on the state’s childcare sector reaching an inflection point. Florida had received more than $3 billion in federal emergency relief funding to support childcare providers and allow parents to return to work at businesses eager to open, TaxWatch warned. “While this funding was absolutely critical, it will be gone by September 2024 — with most of the funds set to expire September 30th (2023) — leaving Florida staring down the edge of a $3-billion fiscal cliff in the absence of additional funding.”

Childcare providers had used the money to pay employees and increase their salaries when post-pandemic inflation struck. The funds also helped keep tuition from rising, so as not to put a further burden on families.

A Florida Chamber study, conducted in partnership with the National Chamber Foundation, found that childcare difficulties for Florida families cost the state’s economy an estimated$5.38 billion each year, including a $911-million annual loss in tax revenue and a $3.47-billion yearly cost to companies due to employee turnover and absenteeism.

The Century Fund, a non-partisan, New York-based think tank, released a state-by-state analysis of the looming childcare cliff, finding more than 200,000 Florida children could lose care with the projected closure of nearly 2,200 childcare programs as the federal money dries up.

“What they (childcare facilities) will have to do is make choices about which services they can offer, where and how much, so it will have a direct impact on capacity,” says Beth Houghton, CEO of the Juvenile Welfare Board of Pinellas County, which partnered with the Pinellas Early Learning Coalition to create scholarships to help families that didn’t qualify for state subsidies.

“They (the centers) rely on payments from parents, from ELC subsidies for maybe some money from us, maybe some philanthropy, but at the end of the day, they’ve got to have enough money to fund salaries and insurance and all the other expenses,” Houghton says. “And all of those things are going up, and I think we absolutely fear that a lot of smaller preschools and daycare centers are going to go out of business.”

Denise Brown’s clients and friends have turned down promotions to stay under income limits for childcare subsidies. These families, she says, face terrible choices: “Do I try to make things better for my family, or do we stay in the same low-level situation” to qualify for assistance? It’s not really what they want to do, but sometimes families are forced to do what they have to do.” The Browns are among the families the United Way of Florida classifies as “ALICE.”

For families the United Way classifies as “ALICE” (Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed) who earn too much to qualify for state or federal aid programs but not enough to afford childcare bills, the uncertainty of what’s to come is only the latest challenge when it comes to their family’s financial stability.

Daytona Beach residents Miracle and Sam Williams each have good, steady jobs: She’s a Volusia County School Board secretary and he is a Walmart grocery team leader. When they married, their combined income of about $75,000 for a blended family of six put them above the limits for a subsidy for their daughter, Samari, to attend Kindercare, a for-profit early childhood education center. Without the aid, the tuition nearly tripled.

Florida’s School Readiness Program, a financial aid program funded primarily by the federal block grant, requires parents to either work or be in an education program for at least 20 hours per week. It cuts off support to families above 150% of the federal poverty level.

Miracle Williams went back to school, earning a bachelor’s degree from Daytona State College. As a student, she again qualified for a subsidy, keeping Samari in the early learning program. That aid disappeared again once Miracle was handed her diploma.

On Tap

Florida lawmakers budgeted $1.6 billion for early learning for the 2023-24 fiscal year. That included: more than $427 million for voluntary prekindergarten (VPK); $1.1 billion for School Readiness; $10 million for T.E.A.C.H. (which provides early childhood teacher scholarships); $4.5 million for Help Me Grow; $3 million for professional development for early-learning teachers; and $3.9 million for the Home Instruction Program for Preschool Youngsters. Gov. Ron DeSantis is proposing $1.6 billion for early learning in next year’s budget.

Legislative Passion Project

Some relief for families struggling to find and afford childcare is coming, assures state Rep. Fiona McFarland (R-Sarasota). Her bill revamping regulations for childcare providers died in the 2023 session, she says, because she “tried to do too much in one bill.” For McFarland, the issue hit close to home: She gave birth to her third son three weeks before the session ended.

The bill is her “passion project,” she says, “because there is no infant care available in Sarasota County where I live. There’s no way that a daycare provider can make money on the care of infants. It streamlines regulations for existing providers with good records and offers incentives for employers who provide or underwrite childcare costs for their workers.”

The Department of Children and Families makes three unannounced inspections at childcare facilities each year that cover 437 items. “I’m fine with inspection if it leads to safety for children and quality of education,” McFarland says. “But there’s no way you can look at me with a straight face and tell me all 437 are drivers of quality or safety.”

To encourage employers to be part of the childcare solution, the legislation would ease regulatory hurdles through exemptions and tax credits covering half the capital costs of building a daycare center. Or, the companies would be able to claim up to $300 per child per month in assistance to attend a private daycare center.

“I want to make this benefit available to the (greatest) number of children and families in Florida that I can,” McFarland says.

Ripple Effect

When families don’t have affordable, quality childcare, it can affect their ability to hold a job and their long-term upward mobility. U.S. Census survey data show a lack of adequate childcare was the main reason unemployed Floridians who want to work don’t. While childcare was more frequently the hurdle for workers whose education stopped at high school — about 34% cited it as an issue — about one-fifth of those surveyed with bachelor’s degrees and more than 11% with graduate degrees said a lack of childcare was keeping them out of the workforce.

It’s also a reason many parents never complete their degrees, says Braulio Colón, Florida College Access Network executive director. FCAN works with the state’s public universities to address barriers to graduation for low-income students and others who don’t fit the “traditional” college student mold.

“Student parents are more likely to miss class or perform poorly,” he says. “Additionally, they can’t fully take advantage of the student resources that lead to student success because they have less time to seek those services. Lastly, cost restraints make them less likely to finish a degree program.”

Colón says on-campus childcare facilities or local partnerships with community organizations could help. “At the institutional level, policies are needed to help destigmatize student parents’ challenges, such as offering tailored academic advising and emergency childcare services,” he says.

Help From Washington Stalls

U.S. Rep. Kathy Castor (D-Tampa) is one of 161 House and Senate Democrats and independents pushing to restore the now-expired Child Care Stabilization program, which she calls a “godsend” that prevented the childcare sector from collapsing. The Child Care Stabilization Act would provide $16 billion each year for the program, but the bill has slim odds of passing in the GOP-controlled House, Castor says. The White House estimates Florida would have stood to receive more than $900 million to support more than 9,000childcare centers. Castor says to stabilize the nation’s childcare system not only do families need economic relief, but childcare workers need training and incentives to help them advance in their jobs. “They’re talented, committed professionals working in our (childcare system) that understand the economic importance of making sure we have parents who can work and children who can thrive,” Castor says. “There is a much wider understanding now the importance of that early childhood brain development and what that means to success in life — not just getting ready for kindergarten and doing alright in elementary school, but your whole trajectory in life.”

How Floridians Pay for Childcare

- Head Start and Early Head Start: Children from birth to age 5 are eligible for the federal program if their families are under the poverty level, about $30,000 for a family of four.

- Florida School Readiness Program: Families must have income under 150% of the poverty threshold — about $45,000 for a family of four — to qualify. The program is funded primarily by the federal Child Care and Development Fund Block Grant.

- Florida VPK: Florida was one of the first states in the country to offer free prekindergarten for all 4-yearolds, regardless of family income. The program covers a half-day instruction during the school year or a total of 300 instructional hours for a summer program.

- Juvenile Welfare Boards and Early Learning Coalitions: Local boards throughout Florida invest in early learning and school readiness programs.

- Parents: Childcare is considered unaffordable by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services if it costs more than 7% of a household’s income. The National Database of Childcare Prices at the U.S. Department of Labor shows that in most of Florida’s large urban counties, parents spend about 14% of their income on childcare. In Florida last year, care costs averaged nearly $11,000 a year for infants, $9,200 for toddlers, $8,000 for preschoolers and $6,800 for school-age children.

Orlando’s Childcare Challenges

If families can come up with the money for care, they have another challenge: finding a center with space for their child.

Almost 40% of Floridians live in a “childcare desert” — defined as communities with limited or no access to quality childcare by Childcare Aware of America, an organization that matches families needing care with a network of providers.

One of those deserts is also one of Florida’s most densely populated with businesses and people — Orlando’s International Drive.

The tourism hub is home to some 1,800 companies and 25,577 residents, 1,500 of whom are children under the age of 5. An additional 4,000 children belong to parents who work within the corridor but don’t live there — and childcare options are few and far between, with only eight providers able to serve 216 children.

The I-Drive corridor was spotlighted in a recent report on wider challenges in the childcare system in Orlando from the Helios Education Foundation, the Early Learning Coalition of Orange County and the K-Ready Community Project, that declared the industry “in serious trouble and unable to meet the childcare needs of all working parents and children in Orange County.”

The report found:

- Chronically low teacher salaries and competition from other employers has led to a shortage of teachers, which in turn has led to lower enrollment at centers and longer waiting lists.

- State subsidies to help cover costs are inadequate, keeping providers from raising teacher pay.

- At least half are operating at enrollment levels below sustainable levels, and the expiration of federal funds that kept many providers afloat has many centers at a “breaking point.” As many as half of the childcare spots in the study area could be at risk.

“This is an untenable situation that the (childcare) industry cannot and should not have to solve on its own,” the report’s authors concluded.

They recommend pilot projects that might develop solutions for the industry. Among their recommendations are developing shared services, business supports and coaching to improve provider financial stability. They also recommend sustainable funding for childcare from a variety of stakeholders, including government, employers and philanthropies.

One of the area’s big employers — hotelier Harris Rosen — has been working on the problem for decades.

Since 1994, he’s provided free preschool to all children ages 2 to 4 living in the nearby Tangelo Park neighborhood. Rosen’s foundation also covers the cost of a college or vocational education for students who grow up in the community — an initiative credited with boosting graduation rates and cutting crime in the neighborhood.

In 2017, he opened a second preschool in Parramore, a historically impoverished community on the edge of downtown Orlando.

The 33,000-sq.-ft. school has a capacity of more than 250 seats dedicated to children who are residents of Parramore. To accommodate parents’ work schedules, it’s open Monday through Friday, year-round, closing only on seven major U.S. holidays.

As he’s done in Tangelo Park, Rosen promises full-ride scholarships to college or vocational school for students who attend his Parramore daycare and go on to graduate from their local high school.

As he makes a dent in the crisis, Rosen is encouraging other companies to replicate his efforts to broaden the impact.

“Businesspeople should be interested in this kind of initiative — call it an investment —because the return on investment is $7 for every dollar invested,” Rosen noted during a 2021 seminar on how businesses can support early childhood education. “No matter what business you are in, it will help your business to adopt a Tangelo Park program, and that’s our hope and that’s our dream.”

Read the article as originally published at https://floridatrend.com/article/39176/daycare-dilemma